Using this guide

This guide serves to help farmers who offer housing to seasonal or temporary workers determine whether OSHA is enforceable against the farm. The guide consists of a flowchart and two checklists. The flowchart provides a basic roadmap to help farmers figure out whether they have a “temporary labor camp” as defined, which subjects their farm to OSHA enforceability. The first checklist breaks this down further by listing and explaining the various factors that come into play. The second checklist outlines the basic housing standards and requirements under OSHA that farms with “temporary labor camps” must follow.

Part 1—Overview

Understanding the issue: Must farmers who provide housing to their workers comply with federal OSHA regulations?

Under the federal Occupational Safety and Health Act, commonly known as OSHA, all private employers are responsible for providing a safe and healthful workplace for their employees. OSHA requirements apply to all farms no matter what. However, back in 1976, Congress passed a bill that prevents the federal Department of Labor (DOL) from enforcing OSHA on small farms that don’t have a “temporary labor camp.” Small farms are defined as those with 10 or fewer employees, not including immediate family members. What does this all mean for these small farms? Technically, they are required to comply with OSHA. However, they face little to no risk because the federal DOL has no right to take enforcement action against them.

Side note: OSHA does not define immediate family members. However, it is generally presumed that the definition in the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) applies. This definition limits family members to the legal spouse, children (biological, step, adopted, foster) and parents (biological, step, adopted, foster).

But wait. The story may be different if you have a small farm and provide housing to your workers. That’s because the DOL can inspect and take enforcement action against any farm, no matter what size, if it has a “temporary labor camp.” What is a temporary labor camp? Many folks picture temporary labor camps as sets of tents or mini temporary structures that house a number of out-of-state or foreign workers. This is not accurate! Temporary labor camps are defined broadly. Basically, they include any housing that is provided to a temporary worker as a condition of employment. In other words, it’s a temporary labor camp if the worker for all intents and purposes has no other choice than to live in the housing provided by the farm based on the location or other circumstances of the job. High or even multiple occupancy is not a necessity for the housing provided to be considered a temporary labor camp. It could just be housing for a single temporary or seasonal worker. Also, the term temporary relates to the worker. The housing itself doesn’t have to be temporary. It could be a permanent structure, including even a single room in the farmer’s house.

The takeaway is that farmers who provide housing to their temporary or seasonal workers need to understand whether this subjects the farm to OSHA enforceability. Farmers should pay attention to their obligations under OSHA. If a farm has a “temporary labor camp” as defined and is not in compliance with obligations under OSHA, the penalties can be serious including hefty fines and even jail time for any violations. Inspections can occur without advance notice.

What about state law? Farm worker safety is an issue that is regulated at both the federal and state levels. Regardless of whether a farm is subject to OSHA enforceability, most farms have to comply with their state’s worker health and safety regulations. These state laws often mirror the federal OSHA requirements. However, some are even more stringent. Farmers need to become familiar with and take steps to comply with the applicable worker health and safety laws in their state.

Farm businesses engaged in agritourism, value-added processing, and other non-farming activities are likely subject to OSHA enforcement action

The federal DOL has also taken the position that it can take enforcement action against farm businesses engaged in non-agricultural activities, such as hosting agritourism events, manufacturing value-added products, and so on. Farmers running diversified farms should make it a priority to become familiar with and comply with the federal OSHA standards. It goes without saying, all farms should be committed to creating and maintaining a safe working environment as well as living quarters for their employees!

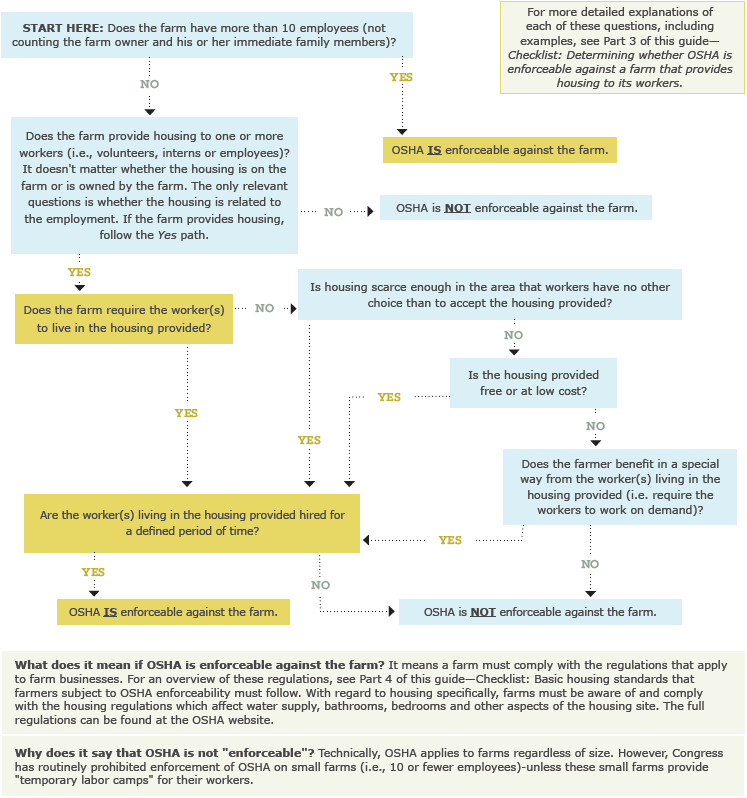

Part 2—Flowchart: Federal OSHA and housing

By providing housing, a farmer may subject the farm to an OSHA inspection. Although OSHA is not generally enforceable against smaller farms, that exception does not apply when housing is provided in a “temporary labor camp.” Use this flowchart to determine if your farm business may be subject to a federal OSHA inspection because you have a “temporary labor camp.” State OSHA laws may apply regardless—this chart does not describe state OSHA regulations.

Part 3—Checklist: Determining whether OSHA is enforceable against a farm that provides housing to its workers

This checklist is for farmers who have 10 or fewer workers and who provide housing to one or more of these workers. It walks through the factors that the federal DOL considers when determining whether the housing arrangement provided constitutes a “temporary labor camp.” If the housing situation is considered a temporary labor camp, OSHA will be enforceable against the farm. If it is not, the farm is still subject to OSHA; however, the federal DOL or applicable state agency has no right to inspect the farm or take enforcement action.

Side note: As both the overview and flowchart explained, OSHA is automatically enforceable against farms with 11 or more employees. When counting employees, immediate family members are excluded (i.e., only the legal spouse, children (biological, step, adopted, foster) and parents (biological, step, adopted, foster) of the farm owner(s)).

Regardless of whether federal OSHA is enforceable against the farm, most farms will be subject to state health and safety laws that are enforceable. These laws often mirror the federal OSHA requirements and in some cases can be even more stringent. Farmers need to be sure to become familiar with and comply with their state’s worker health and safety laws as well as applicable zoning and housing codes.

Does the farm provide housing to worker(s) (i.e., volunteers, interns, or employees)?

It does not matter whether the housing is on the farm or is owned or even controlled by the farm. It simply has to be arranged and provided by the farm. Also, the “temporary” aspect of a labor camp relates to the temporary nature of the employee and not the structure itself. Thus, it could include permanent and temporary structures. Moreover, there is no number requirement. A temporary labor camp could be housing provided for just one worker. Basically, the only relevant question is whether the housing is provided in relation to the employment arrangement. Or, are the folks who are living at the particular housing site doing so because they work on the farm?

Note too that workers in this context generally includes volunteers, interns, and even independent contractors. That’s because in the vast majority of cases, folks who work for farms that operate as for-profit businesses are considered “employees” in the eyes of the law. It does not matter what you call your workers. It also doesn’t matter whether the farm business turns a profit! Basically, folks who work on a farm will be considered “employees” unless one of the three following scenarios applies: (1) the farm is legally recognized as a non-profit organization—in which case you may have unpaid volunteers in certain circumstances, (2) the farm meets the robust legal test for having unpaid interns—in which case you may have unpaid interns, or (3) the farm meets the robust legal test for having independent contractors—in which case federal employment laws generally do not apply. If none of these three scenarios applies, your workers will be deemed employees by the law.

Side note: For more information on volunteers, interns, and independent contractors see Farm Commons’ print resource “Farm Employment Law: Know the basics and make them work for your farm” and our online tutorial “Building a Legally Sound Intern and Volunteer Program for Farm Work.”

Bottom line: This factor is met if the farm provides housing in some form to its workers, which generally includes folks who the farm calls employees, interns, apprentices, volunteers, or even independent contractors.

Is the housing provided directly related to the employment of the folks living there?

Fundamentally, if the housing is in any way a condition of employment or is directly related to the employment of the folks living there, it will be considered a labor camp. The enforcement agency (whether the federal DOL Wage and Hour Division or the relevant state agency) will look at the following factors to determine if this is in fact the case:

Does the farm require worker(s) to live in housing provided by the farm?

This factor is automatically met if the farmer in fact requires the worker to live in the housing provided in order for that worker to work on the farm. The housing is inherently part and parcel of the employment arrangement. In other words, if the worker does not accept the housing provided then the worker has no job there. If this is the case, the housing is undoubtedly related to the employment!

Is housing scarce enough in the area that workers have little other practical choice than to accept farm-approved housing?

Likewise, if for all intents and purposes there is no reasonable alternative housing in the area other than what’s provided by the farm, it will be seen as a condition of employment. Several factors come into play here. It could be that there’s absolutely no other places for miles, for example, if the farm is located in a very remote rural area. It could also be that there’s some housing a few miles away, but there’s no reasonable transportation from the alternative housing to the farm. Finally, it could be that the cost of the alternative housing is unreasonable, and the worker really has no other practical choice than to accept the housing provided. Practically speaking, if these factors come into play, the worker has no choice and is effectively required to live in the housing offered if she wants to work on the farm.

Is the housing provided free or at low cost?

If the housing is provided for free or at a low cost, it will appear to the enforcement agency that the housing is included as an inherent part of the employment arrangement. The lower or free rent is offered as a perk or benefit to lure in more workers. It will therefore generally be considered a labor camp.

Does the farmer specially benefit from the worker(s) living in the housing provided?

It’s generally convenient for the farmer if all her workers are living on or near the farm. The workers are more likely to show up to the worksite on time as they have less distance to travel. They also get more rest, as they don’t have to spend time coming and going. This is all fine. However, if the farmer benefits in special or other more direct ways, the housing will be seen as a condition of employment. A situation where this may arise is if the workers are required to work on demand. For example, if the farmer requires her workers living there to be ready to work at a moment’s notice. Or, if it appears that the farmer is purposely making housing available on or near the farm to ensure that the farm has an adequate supply of labor.

Bottom line: The overarching factor of whether the housing provided is a condition of employment is met if: (1) the farm in fact requires the worker(s) to live in the housing provided, (2) affordable and practical housing in the area is so scarce that the worker essentially has no choice but to live in the housing provided, (3) the housing is provided free or at low cost, or (4) the farmer takes special benefits by having workers living there. Farmers who do not want the housing they provide to be regulated as a temporary labor camp should not explicitly require the workers to live there. They should also be sure other adequate housing is available and charge rent at or near the fair market rate in the area. Finally, they should take care to set appropriate boundaries between work and the housing site so it does not appear that they are taking advantage of or reaping special benefits by having their workers living in the housing provided.

Are the worker(s) living in the housing provided hired for a defined time period?

For it to be a temporary labor camp, it must house “temporary” workers. The term is defined quite broadly. Temporary does not just mean seasonal employees. Rather, it is for any discrete or defined period of time. Temporary could be an employment arrangement for one month, one year, or even 10 years if it is defined and agreed to as such upfront. Temporary is basically anything other than a permanent, indefinite employee relationship.

The reality is that most workers on farms are temporary, unless they work year round and have a formal understanding that they are working indefinitely, or until notified otherwise such as an “at-will” employee. All seasonal employees are considered temporary employees, even if they plan to come back the following year.

Bottom line: If a farmer provides housing to “temporary” employees (i.e., anyone other than an employee who is working on the farm year round and indefinitely), and the housing provided is related to the employment relationship, OSHA standards are enforceable against the farm.

Part 4— Checklist: Basic housing standards that farmers subject to OSHA enforceability must follow

The following checklist provides an overview of the basic OSHA housing standards that could be enforced upon farms that provide housing to their workers that meets all the factors of a “temporary labor camp.” Farmers should be aware that other OSHA standards that are relevant to farms may also be enforced against these farms. A few of these standards are highlighted for general reference.

Failure to comply with OSHA brings serious consequences, including fines and even jail time. The penalty varies depending on the types of violations. The agency can assess a penalty for up to $1,000 for each violation that compromises job safety and health, or up to $7,000 if there’s a likelihood that the violation could cause serious injury or death. If the farmer intentionally violates the standards (e.g., has been warned, but continues to violate them), penalties can be as high as $70,000 and imprisonment up to six months. These laws are not to be taken lightly!

Farmers who have “temporary labor camps” or whose farms are otherwise subject to OSHA enforceability should contact their regional federal DOL office or state agency responsible for more details.

Side note: Technically, all farms must comply with federal OSHA standards. However, only those farms that have 10 or more employees or have a “temporary labor camp” are subject to enforcement actions.

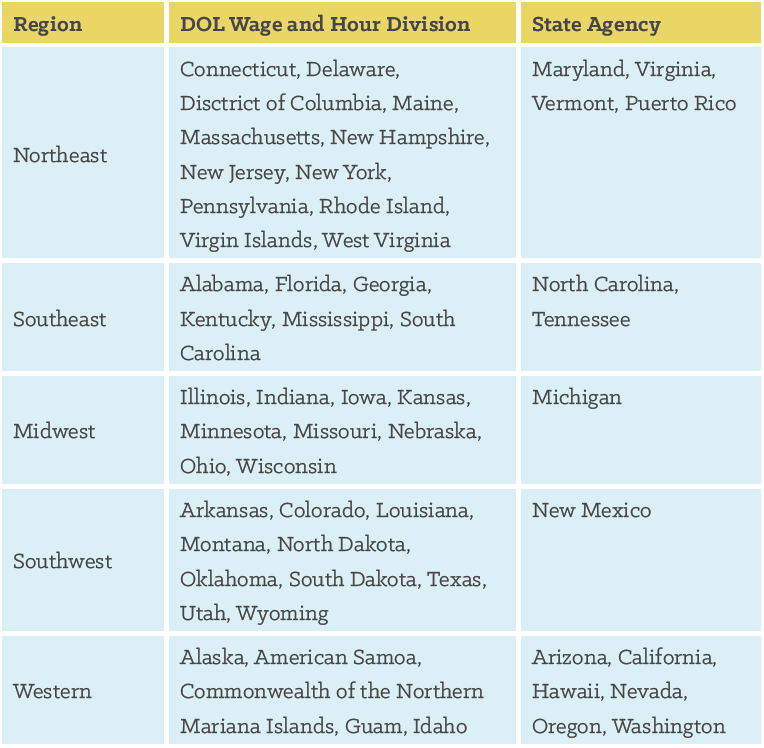

OSHA Enforcement

Depending on the state, the enforcement of the federal OSHA is handled by the federal DOL Wage and Hour Division or a relevant state labor and employment agency. The following chart breaks this down. Farmers should check where their state falls and contact either the regional federal DOL Wage and Hour Division office or their state agency for specific questions and more details on OSHA enforcement.

Side note: The substantive OSHA housing requirements are found at 29 CFR 1910.142.

Housing site

o Is the site adequately drained (stagnating pools, sink holes, or other collections of surface water are at least 200 feet away, drainage through site does not endanger water supply, site is free from depressions where water might accumulate during storms)?

o Is there sufficient water supply (e.g., where is well located, is it adequately sealed to prevent contamination)?

o Are the houses adequately spaced to prevent overcrowding?

o Is the housing site where food is prepared and served and where folks sleep at least 500 feet from any place where livestock are kept?

o Is the site around the houses clean and sanitary (i.e., free from rubbish, debris, garbage, etc.)?

o Are all privy and garbage pits and the ground and buildings left in a sanitary condition at the end of the season (e.g., privy and garbage pits filled with earth and privy buildings locked or otherwise secured to prevent rodents)?

o If public sewers are available at the site, are all sewer lines and flood drains from the building connected (i.e., no sewage seepage is permitted on the ground surface)?

o Are adequate measures taken to prevent infestation and harborage of insects, rodents, and pests?

House or shelter

o Is the house constructed in a way that will provide sufficient protection from the elements (i.e., are roof and walls in good repair)?

o Are beds with clean mattresses or cots provided in every room used for sleeping?

o Are suitable storage facilities provided in every room used for sleeping (such as wall lockers for clothing and personal articles)?

o Are beds properly spaced (i.e., beds must be at least 36 inches apart from each other and at least 12 inches off the floor; bunks must be at least 48 inches apart laterally and front and back with 27 inches of clearance between top and bottom, and no triple-deck bunks)?

o Are floors well-constructed and kept in good repair (i.e., made of wood, asphalt, or concrete; free from splinters, holes, and nails)?

o Are all wooden floors elevated not less than one foot above the ground level at all points to prevent dampness and to permit free circulation of air beneath?

o Are windows provided in each room (must be at least one tenth the size of the floor area)?

o Do windows and outside doors provide proper ventilation (i.e., windows must be able to be opened at least halfway, all windows and outside doors must be equipped with 16-mesh screens, all screens on doors must be self-closing)?

o Does each room used for sleeping have at least 50 square feet of floor space for each occupant?

o Does the house where workers cook, live, and sleep have a minimum floor space of 100 square feet per person and at least a seven-foot ceiling?

o Are sanitary facilities for storing and preparing food provided in each family unit (i.e., kitchen must contain cupboards or shelves, table and chairs, and a working refrigerator)?

o Is the heating, cooking, and water heating equipment installed in accordance with applicable state and local ordinances, codes, and regulations?

o If the house is used during cold weather, is adequate heating provided?

o Does each site have a working stove or facilities for cooking and heating water (for multi-family units, are cooking facilities provided for each unit)?

o If electricity is available at the housing site, does each habitable room in the house have at least one ceiling-type light fixture and electric receptacle?

o Does each housing site have an adequate and convenient water supply for drinking, cooking, bathing, and laundry (i.e., water must be available within 100 feet of the house if not piped to the house and supply must be capable of delivering 35 gallons per person per day to the campsite at a peak rate of two and a half times the average hourly demand)?

o Has drinking water supply been approved by the appropriate health authority?

Toilet facilities

o Is there at least one toilet facility for every 15 people?

o Is each toilet room satisfactorily ventilated (e.g., has a window not less than six square feet in area opening directly to the outside area or is otherwise satisfactorily ventilated with a screen)?

o Are outdoor toilets located within 200 feet of the shelter but no closer than 100 feet?

o If toilet rooms are shared (e.g., multi-family and barracks-type facilities) are separate toilet facilities provided and marked for each gender?

o Does each toilet room or outdoor privy have safe and adequate lighting for use at all hours?

o Is toilet paper available at each toilet privy or room?

o Is each privy or toilet room kept in a sanitary condition?

• Laundry, handwashing, and bathing facilities

o Does each house have a handwashing basin (or one basin for each six persons in shared facilities)?

o Does each site have a shower facility (or one shower head for each 10 persons in shared facilities)?

o Does each site have a laundry tray or tub for every 30 persons?

o Is there a slop sink in each service building for laundry, handwashing, and bathing?

o Is there an adequate supply of hot and cold running water provided at each site for bathing and laundry purposes?

o Are facilities (clothesline or dryer) provided at each site for drying clothes?

o Are floors in laundry rooms of smooth finish (but not slipper) and impervious to moisture?

o Are floor drains provided in all shower baths, shower rooms, and laundry rooms to remove waste water and facilitate cleaning?

o Are the walls and partitions of shower rooms smooth and impervious up to the height of the splash?

o Are junctions between the curbing and shower floor covered?

o If a central service building is used for laundry or bathing, does it have equipment capable of maintaining a temperature of at least 70 F during cold weather?

o Are all service buildings (laundry, shower, etc.) being kept clean?

o Does each laundry room and bathroom have at least one ceiling or wall-type light fixture and electric receptacle?

Refuse disposal

o Are garbage cans available at each site and are they fly-tight and rodent-tight (i.e., must have adequate lids)?

o Is at least one garbage can or disposal source available for each house (i.e., located within 100 feet of the house)?

o Are garbage containers kept clean?

o Are garbage cans placed on a wooden, metal, or concrete stand?

o Are garbage containers emptied when full, but not less than weekly when in use?

First aid and health

o Is a first aid kit available at the site for the emergency treatment of injured persons?

o Is the farmer aware that she or he must immediately report to the local health office the name of any individual at the site who is known or suspected of having a communicable disease?

o Is the farmer aware that she or he must immediately call the nearest health authority to report any case of suspected food poisoning or an unusual prevalence of fever, diarrhea, sore throat, vomiting, or jaundice?

Other relevant OSHA requirements for farms

o Storage and handling of anhydrous ammonia

o Pulpwood logging

o Slow-moving vehicles (tractors, etc.)

o Tractors and other vehicles with the potential to roll over

o Moving machinery parts of farm field equipment, farmstead equipment, and cotton gins

o Toxic and hazardous substances involved in exposure to cotton dust

o Toxic and hazardous substances in general

o Improper field sanitation

o Signs, record keeping, injury reporting, and first aid training

Side note: The details of these other OSHA requirements can be found at 29 C.F.R. Part 1928.